In the mountains of the Balkans, up until the end of the 20th century, shepherds carried with them a calendar stick. It was a stick with a notch cut into it for every day of the year and a cross or some other symbol for

major holy days, which in Serbia are all linked to major agricultural

events and major solar cycle events. At the end of every day a piece of the stick up to the first notch, representing the previous day, was cut off from the stick. When the last piece was cut, the year was over. This was a very effective

way to track the passage of time. It was simple and could have been used easily by uneducated shepherds in the mountains where they were often cut off from the rest of the population for up to nine months. By looking at the stick they would know when it is time to praise god and their protector saint. But also the would know when the cheese needs to be ready and packed so that it can be sent from the mountain stations down to the valleys. And when to gather the flocks for sheering and when to start migrating down to the valleys before the winter descends.

Two shepherds minding flocks on the mountain would be able to coordinate their actions with each other and with the people from the valleys by using identical calendar sticks.

But in order to make these calendar sticks, you need to know:

1. When does the solar year start?

2. How many full moons there are in a year?

3. How many days there are in a moon?

4. How many full moons are in a solar year?

5. How many full extra days there are after the end of the last full moon before the beginning of the new solar year?

Once you know this, you can make a stick calendar, give it to people and they will be able to coordinate their actions. Here is an example of the stick calendar from Bulgaria.

How do you determine all the above? By a very long period of observation of the sun and the moon and their changes, and by realizing that they follow cyclical patterns. Then you need to determine what these cycles are and how they relate to each other.

Easy.

You realize that there is a day and a night. Day always fallows night and night always fallows day. So you can use a border moment between night and day, sunset or sunrise as delimiting point which determines the beginning or the end of a day and night period. Then you can count days by counting the number of sunrises or sunsets. You have your time unit that you can use for measuring and expressing time. So you find a level place from where you can observe the sunrise and sunset all year round and start observing and counting. You want to mark the place from which you are observing the sky, so you use a stick, a post and stick it into the ground. So every morning you go to the post and observe the sun rising and every evening you go to the post and observe sun setting.

You also realize that there is this body in the sky, moon and that as night after night passes, moon changes from a thin crescent to the full circle and back again.

Then one night during the full moon you start wandering after how many nights the moon will become full again. You take a stick (štap in Serbian) and you cut a notch into it for every night between the two full moons. Now you have a full moon cycle cut "into stick", or cut "u štap" in Serbian. The archaic word for full moon in Serbian is still "uštap", meaning "into stick". You then repeat your marking of nights into another stick "štap" for the next moon cycle and the next. You compare your moon sticks "uštaps" and you realize that the full moon always comes after the same number of notches.

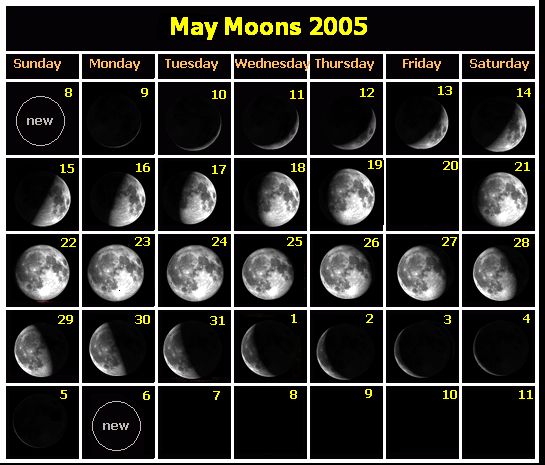

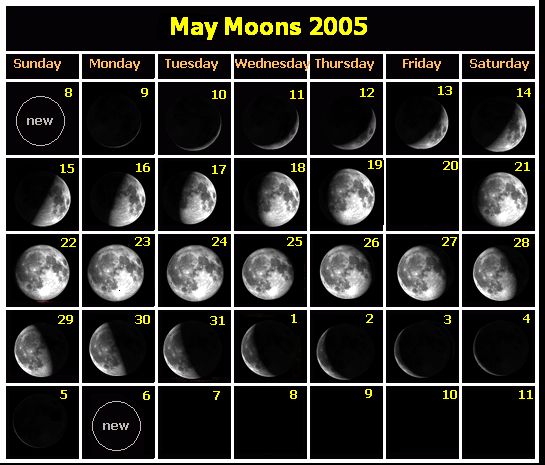

The Moon has phases because it orbits Earth, which causes the portion we see illuminated to change. The Moon takes 27.3 days to orbit Earth, but the lunar phase cycle (from new moon to new moon or from full moon to full moon) is 29.5 days. The Moon spends the extra 2.2 days "catching up" because Earth travels about 45 million miles around the Sun during the time the Moon completes one orbit around Earth.

You count notches on your moon stick, your "uštap". You realize that the there are about 29 to 30 nights in a moon cycle. You start calling this period moon (mesec in Serbian). And you have a lunar calendar.

Because the first day counting was associated with moon cycle calculation, the start of the day was counted from the sunset. This tradition was preserved in both Ireland and Serbia until very recently.

Because the tracking the change of the moon is easy, the first calendars were moon based. You could say to people: "we will meet at the next full moon" or "we will meet three full moons from today" or "we need to meet on the third day after the third full moon". All people needed to do to keep their appointment was to use stick "štap" and mark the passing of full moons into the stick "uštap".

Alexander Marshack, in a controversial reading, believed that marks on a bone baton (c. 25,000 BC) represented a lunar calendar. Other marked bones may also represent lunar calendars. This is the Blanchard bone.

Similarly, Michael Rappenglueck believes that marks on a 15,000-year old cave painting represent a lunar calendar. The below picture is from the Lascaux cave in France. The dots in the picture are supposed to be representations of days in the 29 days moon cycle.

This is a very good article arguing that the cave paintings in Lascaux represent a complex lunisolar calendar. I have my doubts mostly because the described system is too complicated. There is a much easier way to use sun and moon to calculate time.

This is the 8000 years old lunar calendar found in Serbia. It is made from the tusk of a wild boar and is marked with engravings thought to denote a lunar cycle of 28 days, as well as the four phases of the moon. There is an empty space just before the last notch. Is this the 29th day, when the new moon vanishes from the sky and is not visible? The calendar fits into a pouch or a small bag so it can be said that this is probably the world's first pocket calculator, calendar.

The area where the tusk was discovered represents one of Europe's most interesting archaeological sites from the Neolithic period and was a religious center 8,000 years ago.

This was probably a ceremonial calendar, which probably belonged to the priest and was maybe even held in a temple. The ordinary people probably had "uštap" the full moon cycle cut into a stick. For time synchronization required for work planning simple "uštap" is perfectly sufficient. There is no need for time adjustment

The problem is that this system is good enough for short term planning which is not related to the vegetative cycle. But if you try to use moon calendar to plan your activities related to vegetative cycle you will realize that the moon calendar is not the right tool for the job, because the Earth vegetative cycle is governed not by the moon but by the Sun. If a specific solar governed event, like the beginning of spring fell on the 3rd full moon this year, it will not fall on the 3rd full moon next year. Because the lunar year, the sum of full moons in one year, is shorter than the solar year, the new lunar year will start earlier than the solar year and the solar event will occur later than previous year. And this lagging of the solar events will be bigger and bigger as years pass.

So how do you solve this problem?

You realize that you need to start using the sun cycle in order to determine the exact timing of vegetative events during the solar year. You start with what you know about the sun. You know that the sun is changing in a longer cycle. It gets higher over the horizon and hotter and then lower and colder over many moons. The trick is to determine exactly when the solar cycle starts and how many moons does it last.

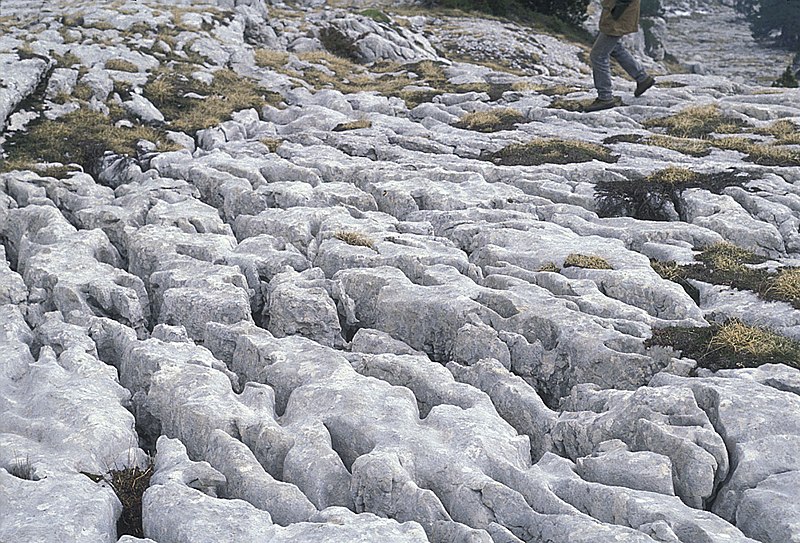

Remember the level place from where you were observing the sunrise and sunset all year round in order to determine the number of days in a moon? The observatory? You are standing next to the observation pole and observing sunrises and sunsets. As you are observing the sunrises and sunsets, you notice that the point where sun rises is not the same as the point where sun sets. The sun rises on the left side of the horizon, travels across the sky from left to right and sets at the opposite right side of the horizon. As days pass you realize that the point where the sun rises moves along the horizon. So does the point where the sun sets. You notice that the sunrise point moves during the spring further and further to the left and the sunset point further and further to the right. So the sun needs to travel longer across the sky and the day is longer and longer and hotter and hotter. Then at some point during the summer the sunrise and sunset points start moving in the opposite direction. The sunrise point starts moving to the right and sunset point starts moving to the left. They get closer and closer to each other, so the sun has to travel shorter distance between the sunrise and sunset and the day is shorter and shorter and colder and colder.

This is extremely important observation if you depend on solar vegetative cycle for your survival. If the length and heat of the day depends on the position of the sunrise and sunset points, then determining how they move becomes imperative. You know that the days when the sunrise and sunset points change the direction of their movements, fall in the middle of the coldest and hottest part of the year. You are of course more interested in the turning point which falls in the middle of the cold dark part of the year. You want to know if, and this was for our ancestors very real IF, and when the sunrise and sunset points will start moving further and further away from each other, because that will mean that the days will start getting longer and hotter again. So you start observing the the horizon and you try to remember where the sun rose and set yesterday in order to compare it with the sunrise and sunset position today. But that is difficult and imprecise. It would be much better if you could mark the points of sunrise and sunset every day in some way and then observe the relative position of the sunrise and sunset points to the marks. So you decide to use two stakes, poles as markers. But it is difficult to mark the exact point of sunrise and sunset if the horizon is uneven. It would be much easier if the horizon is horizontal, smooth and elevated all around you so that the observation and marking of the sunrise and sunset points becomes more precise. So you decide to create an artificial horizontal smooth horizon which will mask the real horizon. You take a long enough rope, tie it to the observation pole and then walk around the observation pole. As you walk you mark a circle with the center in the observation pole.

You then dig a circular trench along the circle and pile up the the dug out earth on the edge of the circle to form the bank. You build a henge like this original earthen henge in Stonehenge. You can read my article about henges here.

Now when the sun rises or sets it will be easy to mark the exact spot of sunrise and sunset with a stake stuck into the elevated earthen bank. Every morning and evening you observe the new position of the sunrise and sunset points. If the sun does not rise and set at the points marked with the yesterday's stakes, you stick new stakes into the earthen bank to mark the new position of the sunrise and sunset points, and you remove the yesterday's stakes. As the days get colder and colder, the sunrise and sunset stakes will get closer and closer to each other. Then one day in the middle of the winter, the movement of the sunrise and sunset points will stop. The sun will rise at the same position behind the yesterday's sunrise stake and will set at the same position behind the yesterday's sunset stake. That day is the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. You mark these two points with the permanent taller stakes. So when the sun again rises and sets behind these two sunrise and sunset stakes you will know that the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the shortest day has arrived again. You can now build a high wall, a fence, a palisade made of wooden stakes, around the central observation stake, within the earthen henge, in order to create artificial smooth horizontal elevated horizon to completely mask the real horizon. You then make two gates, both in the earthen bank and in the wooden palisade within it, at the exact places where the winter solstice turning point stakes were. So in the future, on the day of the winter turning point, the winter solstice, the people standing in the center of the sun circle will see the sun rise and set through the "sun gates".

This is exactly what people did in Goseck circle one of the oldest henge solar observatories in the world.

At the winter solstice, observers at the center would have seen the sun rise and set through the southeast and southwest gates.

You can do exactly the same with the boundary turning points in the middle of the summer. You can make gates at these two points or just at the summer solstice sunrise point and watch the sun rise through the sun gate every summer solstice like in so many henges in England.

Now you have a ceremonial sun circle, which can be used year after year to determine the the beginning of the solar year but also for worshiping of the high god, the Sun.

Then from the starting point of the winter solstice, you count number of days and number of full moons until the next starting point. You get a long stick and you cut a notch for every day and a cross for a full moon day. You are basically determining the number of days in a solar year and the number of "moons" in a solar year and you record them "u štap" in a stick. Next time the winter solstice arrives, you will know exactly how many full moons there are in a solar year and how many "extra" days are you need to reach the end of the solar year. Then when the sun rises through the sun gate, and the new solar year begins, a celebration is held to celebrate the rebirth of the sun and the new year calendar stick is cut.

How was this year calendar stick cut?

The year stick was cut in such a way that it first counted the days of full moons from the day of the winter solstice, regardless whether there was actually a full moon or not. A notch was made for every day and every time the number of days in a full was reached, the full moon mark was made in the calendar stick. At the end of the last full moon period, people were left with the extra days, the days which they needed to add to reach the number of days in the solar year. These days were added to the end of the calendar stick. These extra days were called "dead days". They were outside the calendar, outside the time, between the sun circle and the moon circle. These were the days when no work was done, the taboo days, when everyone was at the sun circle, waiting for the sun to be "reborn" and for another solar year to start. People originally probably used the 29 days full moons. This calendar had 12 full moons and 17 extra dead days. At some point one day was added to each full moon and moons ended up having 30 days each. This calendar had 12 full moons and 5 extra dead days.

In Serbian tradition the name of these 5 extra "dead days" is preserved as (Mratinci, Mrt + den, literally dead day) which in Serbian Orthodox church calendar fall between the 9. do 14. of November. These dead days are also called "vučji dani" or wolf days.

The calendar stick with all the days of the solar year divided into the days of the full moons and the dead days, allowed everyone to count time in the same way, and to coordinate their actions without the need to observe the sky and know anything about the movements of the sun and moon. Now vegetative events of the solar year were fixed in the lunar calendar. Also this system made sure that every year was a true solar year, starting at the exactly the right time and lasting exactly the same number of lunar calendar days. It was the dead days at the end of the solar year that allowed year length adjustment.

So after the celebration at the sun circle is finished, everyone goes away to their villages, bringing with them their year stick calendars. Every day, they cut away a piece of the year stick up to the first notch, marking the passing of the previous day. Then one day, when the last full moon mark is reached on the stick, at the beginning of the dead days, everyone comes back to the sun circle to witness the rebirth of the sun, and to get the new calendar stick carved for them. I love the way these calendars are not made to record the past, but to fix the present moment in time and to allow planning for the future.

It seems that at some stage the order of "dead days" and full moons was reversed and the dead days were counted as the first days after the winter solstice.

In Serbian tradition, Sun, the "Višnji Bog", the High God, is perceived as a living being, which is born every year in the winter. He then grows into a young man Jarilo on the 6th of May the day of the strongest vegetative, reproductive power of the sun. Then he becomes the powerful ruler Vid at the summer solstice, 21st of June the longest day of the year. He then becomes the terrible warrior Perun on the 2nd of August the hottest day of the year. Then the Sun God dies on the day of the winter solstice, the 21st of December the shortest day of the year. The Sun God then goes into the underworld, where it spends 5 days and emerges, reborn on the 25th of December. These 5 days that the sun spends in the underworld, are the extra days, the dead days, the days which are outside of the calendar.

This is why Christ the Son God, was born on the 25th of December, the same day when Mithra the Sun God was born before him.

Epiphany which traditionally falls on January 6, is a Christian feast day that celebrates the revelation of God the Son as a human being in Jesus Christ. The earliest reference to Epiphany as a Christian feast was in A.D. 361, by Ammianus Marcellinus St. Epiphanius says that January 6 is hemera genethlion toutestin epiphanion (Christ's "Birthday; that is, His Epiphany"). Alternative names for the feast in Greek include η Ημέρα των Φώτων, i Imera ton Foton (modern Greek pronunciation), hē hēmera tōn phōtōn (restored classic pronunciation), "The Day of the Lights", and τα Φώτα, ta Fota, "The Lights".

Was the night between the 6th and the 7th of January, the old end of the 17 dead days, when the month had 29 days? The day when the sun reappeared from the underworld and revealed itself to the people as the beginning of a first day of the first moon of the new year? Is this why this day is still a holy day of the revelation, birthday of the Son the God who replaced Sun God? Is this why this day is called the Day of the Lights?

But in Serbian tradition we also find the 5 dead days at the end of the solar year. When the beginning of the year was moved to the spring Equinox in March, the dead days became the Baba's days, the days of the Baba Mara, Mora, Morana, Marzana, the goddess of winter and death. They are the last 5 days of winter, the dead days after the end of the last 30 days full moon and just before the beginning of the spring. In Serbia these days are often in legends called jarići meaning billy goats. Now vanished stone circle from the south of Serbia was recorded as being called Baba i jarići. Baba was the central stone pillar and jarići were the circle stones. Were there five of them? Is this why so many stone circles from Ireland have exactly 5 stones? Maybe these were days during which Jarilo, the young sun, the god of spring is going through the underworld before being born to start new vegetative cycle. There is an expression in Serbia, which probably dates to the time of the forced Christianization of the Serbs in 13th Century: "Ja ga krstim a on jariće broji" meaning "I am baptizing him and he is still counting billy goats". The expression means wasting time on someone and shows how strong the old faith was among the Serbs. Are the billy goats from this expression the same 5 dead days of the old calendar? Are all these beliefs and customs echos from the days when first henges were built 7000 years ago in order to create the first lunisolar calendar?